|

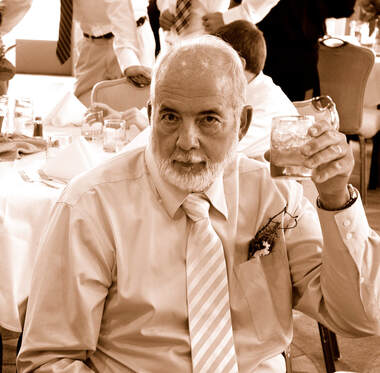

One of my earliest memories of my father is when I was perhaps two or three. We were at a church dance, a father-daughter event. I was too small to dance, so he tucked me in his jacket, buttoning me to his chest; then he danced us both to a poorly played waltz, like I was a queen in my reluctant ruffles, and he was a prince with roasted potato and sweet onion breath from the potluck. I remember his beard being scratchy, his chuckle raspy. I had never been so happy. My father chastises me in bass G, and laughs at his own jokes in a middle baritone D. He whistles when he’s happy. He laments, compassionately soothing other peoples’ worries in a gravelly low C, and warm hug. He taught me about energy, photography, pretty stones, and people. He showed me how to use my cameras, shoot a gun, and change a tire. He understood my need to find things out for myself—so when I’d ask a question, or grip onto a puzzle, he’d grumble in a hoarse b minor and say, “What do you think, you odd little duck? You tell me.” He gave me my love of travel, so I associate the D3 hum of rubber on asphalt, and the E4 of a six-cylinder engine in fifth gear with his road-trip chats, while I aired my feet out the passenger window across the most impressive byways of the Rocky Mountains. On these trips he also gave me Led Zeppelin, and Bach (on opposite sides of the same cassette), and his undying crush… Bette Midler. My father never had a day of musical training in his 75 years, but to me, because I adore him, he is the perfect compositional arrangement. I’ll be 44 on August 5th, this year and my father has never told me I’m beautiful, not even on my wedding day when he gave me away to another man. I never felt the void of that conventional statement other fathers generally give their daughters, because I felt beautiful in the resonance of my soul pitch in direct relationship to his. I saw it in his smile. His tone was pure, his note steady, unwavering. To be honest, the fact that he never needed to say it, and I never felt the lack of it, only proves how well matched our chords synchronized in this lifetime. We had harmony. I say had, because with all great scores, there is a transition key. A point when the notes tremble and the tempo shifts. My father is touched by Mnemosyne’s Curse, and so his linear timeline has fractured. It began about a decade ago, so I’ve had time to reconcile how I want his final days to be remembered. In the beginning, I was angry, grief-stricken, and full of pounding staccato rage at the life theft implied in his diagnosis. Minor, dissonant keys and chaotic mismatched chords and syncopated rhythms tarnished our conversations. I usually left in a mess of tears, believing I had lost him, even though he is still struggling to hold on to this reality, he cannot leave his children behind just yet. I sense he needs us settled so that he can rest. There was a great chasm, a long empty drift in our connection right after his announcement. Over time, I realized the bitter blessing in this stage of his life; he only remembers me as I was in his favorite recollections, those moments he repeats to me again and again. They are often not my favorite or brightest moments… that’s not important, because they are clearly his. What his fractured timelines brings up, I am able to see through his eyes, the dolce delivery of our history as father and daughter, as his final refrains are moments when he watched me grow beyond needing him. When I took my steps to become a woman of this world. When I stretched myself to find a purpose and fulfillment. His repeats are the moments he was most proud of the fact that I surpassed him in love, building community, or chasing my own dreams; dreams he had been too afraid to reach for himself. I somehow, unintentionally, gave him the coherence he was searching for on his fatherhood quest—his voice is full of song when he shares those memories. He’s so far gone, I cannot expect him to understand that I only achieved those dreams because I stood on his firm resonance, his bass voice and sturdy tones. He was the foundation from which I found the courage to leap. I sometimes wish for him the clarity to understand what I mean when I tell him, “We did it, Dad. You did it. You broke the cycle. It’s okay to rest. Take a break.” On a good day, I have about an hour with him. On a bad day, his memory resets every six minutes or so. On those days, when he resets, I say first thing, “I love you, Dad.” Each time his voice lights up, and he says he loves me too, like I haven’t just told him every six minutes for the last hour. It’s just as newsworthy and welcome to him each time—so I am happy to say it as often as it delights. When 44 years is distilled into six-minute intervals, there’s no room left for blame, or accusations, complaints or judgment. There’s no room for regret. There’s only redemption, forgiveness, and acceptance. There’s only enough meter for gratitude. I realize now that his refrains, those looping moments are his last dance with me. Our waltz is a very long goodbye. Over the years the waltz has gotten slower, legato, softer. I take time to cherish it. This disease he wrestles with has purified all emotion and memory into its most crystalline integrity. Neither of us are the youthful people setting out to discover a lifelong friendship anymore; me in my reluctant ruffles, and he with the raspy chuckle and sweet onion breath. Our duet and final meanderings in ¾ time of six-minute intervals around a room are conversations of old events, hazy with displacement, rich in love. And really, why do we do anything at all, if not for that? For that perfectly synchronized harmonic merging of notes into a powerfully unbreakable chord? I apologize for the nostalgia. It’s fresh on my mind, as it’s my dad’s birthday today, so the language/music is easy to access. The point is, we are all a collection of sounds, as you know. Sounds that are meaningless, unless in connection to or relationship to someone or something else. Only in the interactions do we become chords, and keys, and rhythms, even if that connection or relationship is internal, spiritual. That music and language can affect the human body without touching it, is the closest definition to what I might call divinity. My father was a violent and religious man in his youth. During his mid-point reversal, he went down a different path, a spiritual walkabout to discover the divine feminine and Eastern philosophy. He gave away his guns and swore a path of passive non-violence. He sought a newer kind of salvation. In doing so, he had to leave the God he’d loved, and the church that had been his home to embrace totality. Thus it is that I learned about divinity, not God, but music and language and the principles of agape, bliss, and eternal grace from a man who’d forsaken the pulpit—to give his daughters, whom he named after goddesses, a better chance of success in a man’s world. If that’s not the very definition of an Aria… I don’t know what is. (The song of my father. Excerpt from musical scoring notes and musical theory study)- Athena

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorAthena lives and writes in the Siuslaw Forest, Oregon. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed